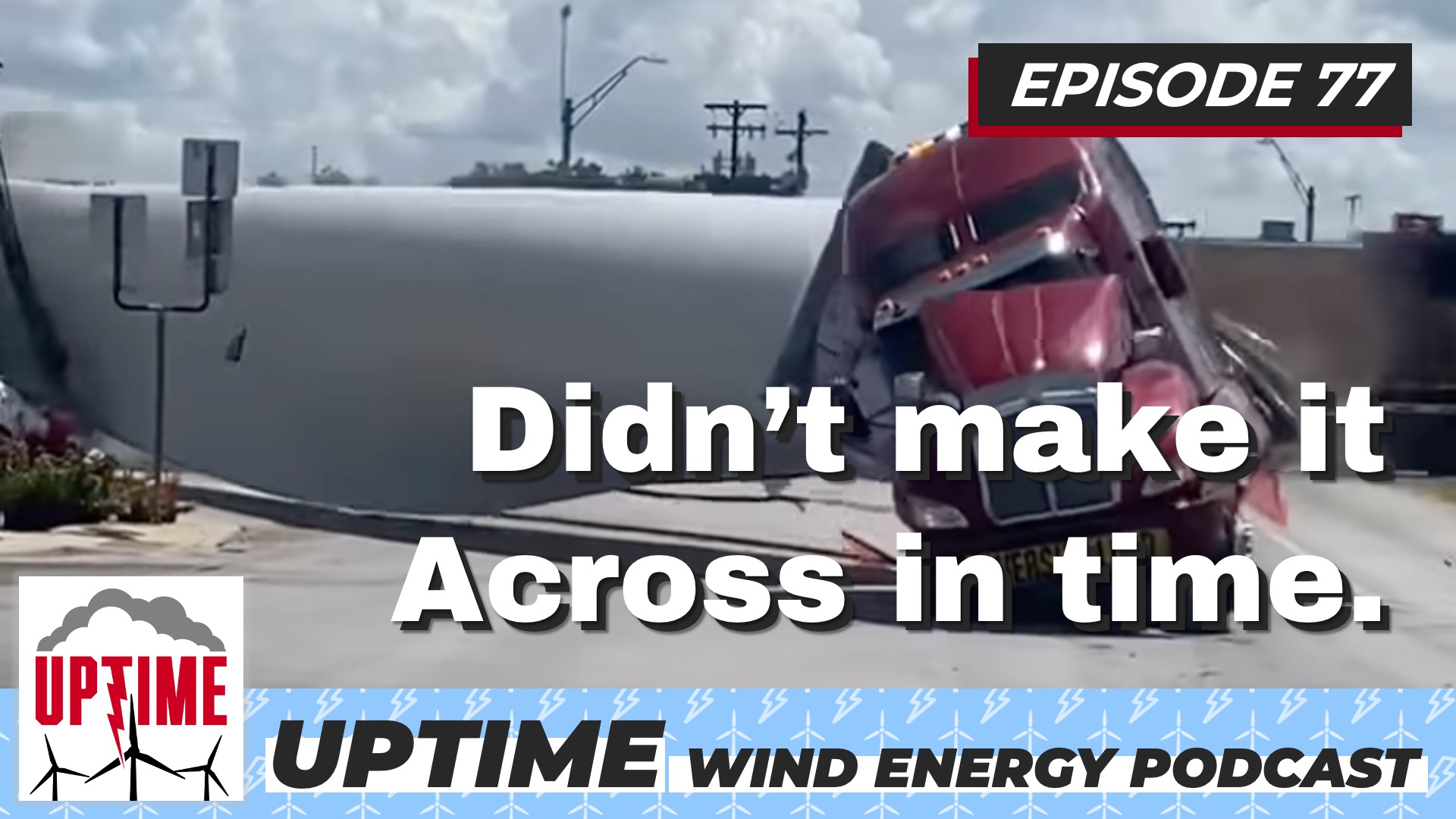

A train collided with a wind turbine blade while in transport on a flat-bed truck. It was a scary situation, and fortunately no one was hurt. But why did it happen? Sea Floor mapping drone technology is improving – what will this mean for offshore wind? We also discuss the Jones Act being invoked in wind installations off the U.S. coast, and whether or not thermoset composites can actually be re-used.

Sign up now for Uptime Tech News, our weekly email update on all things wind technology. This episode is sponsored by Weather Guard Lightning tech. Learn more about Weather Guard’s StrikeTape Wind Turbine LPS retrofit. Follow the show on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Linkedin and visit Weather Guard on the web. And subscribe to Rosemary Barnes’ YouTube channel here. Have a question we can answer on the show? Email us!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Transcript – EP77

This episode is brought to you by weather guard lightning tech at Weather Guard. We make lightning protection easy. If you’re wind turbines or do for maintenance or repairs, install our strike tape retrofit LPS upgrade. At the same time, a strike tape installation is the quick, easy solution that provides a dramatic, long lasting boost to the factory lightning

protection system. Forward thinking wind site owners install strike tape today to increase uptime tomorrow. Learn more in the show notes of today’s podcast. Welcome back. I’m Dan Blewett.

I’m Allen Hall.

And I’m Rosemary Barnes

And this is the uptime podcast bringing you the latest in wind energy, tech news and policy. All right, welcome back to the Side podcast. I’m your co-host and blew it on today’s show. We are going to talk a little bit about the construction process and some of the things that can go wrong, unfortunately.

You know, we’ve got a recent story of a train colliding with a truck carrying a wind turbine blade. So this is obviously bring a big spotlight to, you know, just some of the difficult logistics and the overall sort of construction environment where there’s so many pieces involved, so much going on.

We’ll talk a little bit about that today. We’re talking a little more about wind turbine blade recycling. Vestas has an initiative, as does Siemens, Gamesa for the Future. We’ll talk about the Jones Act as it’s dealing with offshore wind, some sea floor mapping drones and a little bit about this offshore open hydro tidal turbine that’s now being

removed from the ocean. And before we get going, I just wanna remind you that in the description on this podcast, you’ll find uptime tech news, which is our weekly newsletter update for our podcast and other great news are on the website if you want to stay updated with everything.

Definitely jump into the links, whether you’re on YouTube or Spotify, iTunes, Stitcher, and sign up for uptime tech news. Like I said, we want to keep you updated that way. You have a great newsletter from us every Thursday morning, depending on where you are in the world, just to keep you up to date.

And you’ll also find Rosemary Barnes’s YouTube channel, where she is continuing to put out great renewable energy content. So Rosemary and Allan are here with us. So let’s start with this train, Rosemary. How did you feel seeing this train collide with this poor wind turbine blade driver?

Yeah, I felt really sick. And in the the first view of it that I watched, the the guy who stuck taking the film is just going, oh, my God, oh, my God, oh, my God. And that is like exactly mirrored what I was saying in my head.

So I can’t imagine what he was. But the truck driver was thinking, as you know, he’s trying to get out of there and then the train comes. And then Allan was kind enough to send me a second angle of it from behind.

So I really got the full, full 3D effect. And it’s just absolutely shocking, isn’t it? But I was so I was so happy to say that no one was injured somehow. No one was injured in that accident except for the know wind turbine blade.

But that can be replaced, at least.

You think most of these things when they’re transporting such a big blade, obviously, that they have like these couple of cars that trail on like these flag cars. It’s a really big process getting them moved. Why why did this even have a chance of happening?

Well, just looking at the map of Texas, where this event happened, it’s a smaller town. And what it looked like they were trying to do was trying to get from one highway to the other through town and the way that town was constructed there, some gas stations and some obstacles right along the corner.

So it’s very hard to kind of make the turn on the proper road. So what it looked like they were doing was kind of going behind the buildings, kind of squirting behind the buildings next to the railroad track and then cutting across the railroad tracks to get back on the road again.

And just bad timing. I think either they didn’t know what the train schedule was or that it hadn’t arranged it with with the train guys. And timing was everything. You could see in the video, you can actually see the crossing guard start to close.

And everybody around there can hear the train coming in Texas. You can hear him for miles and feel them, too. And so they knew what was going to happen. And I was a little shocked that the trucks didn’t start moving on a bit sooner.

They knew that was coming or maybe maybe he didn’t know it was coming. But it seemed like at the last second we put some gas on the semi and pulled it forward, which is probably the best scenario. It probably actually saved some lives, honestly, because where the train hit that winter and blamers close to the end, if

they had to hit it like square in the middle, you could’ve had a train derailment. What could have been a lot lot worse. So even though it was a bad situation, you know, this is actually not as bad as it necessarily could have been.

Yeah. And I could see it like the blade, the way it bent when it hit, because obviously it’s meant to have a lot of flex in it or at least some degree of flex. I mean, if it hit in the center, it could have been 50 meters a blade, like essentially like wiping out the people, like flinging

them aside essentially off like, you know, and just crushing anything on both sides of that tracks. It’s so

heavy. Yeah. Then in the images of the train hitting, it looks like it’s tossed like it’s a vehicle. And that piece of blade, it weighs more than a vehicle does. And whatever it hit afterwards, I’m sure those damages, damage to buildings down along the railroad tracks.

It looks like there was some closer buildings along the railroad tracks further down. So there’s a whole bunch of cleanup to do. And, you know, in the state of Texas, there’s going to be a lot of oversight about this to try to figure out what happened and try to get safety bulletins out and make sure, one, make

sure he had the proper licenses and authority to be there and to try to make sure that doesn’t happen again. So, Rosemary,

when a blade leaves the factory, I mean, what are the next steps? I’m sure a lot of us just like mundane stuff, like paperwork and, you know, getting where it needs to go, but there’s probably been a big evolution just how these are carted off, hasn’t there?

Yeah, well, I’ve actually had like more experience than I’d like with the logistics departments who take care of what happens to the flight after it leaves the factory, because every blade that I was working on was a prototype blade.

Right. So we doing something for the first time in there. And the logistics team want to know exactly when it’s leaving the factory. Normally they do. And they precisely plan a route so that, you know, they can arrange for a for train crossings to be closed and that sort of thing.

Also, they’re trying to get, you know, cheap rates on on ships. If you just, you know, show up and want to get on the next ship, that’s a lot more expensive than if you can slot into something that’s got a little bit of space free.

Yeah. So when if, for example, you’re involved in a project that was supposed to be finished and, you know, like the end of July, but you’ve got problems and then, you know, it’s pushing out of waka waka waka waka wake, then you’re definitely going to get the logistics team from your customer calling you very frequently to find

out exactly exactly what day your plate is going to be leaving. So. Yeah, that can be the pretty stressful. And then I have to say, I on the projects that I worked on, I don’t know. People started to think that I was coerced because every every time that I would be working on putting up a prototype wind

turbine with some new product on it, something would happen. So I saw blades that got because I was always going to snowy areas, whether the roads are I see it that, you know, trying to get in before winter.

But of course, the schedule blows out. So you’re always arriving just as winter starting roads. I see big trucks. Someone always drove a blade into a ditch. That’s just constantly happened. I also experience accidents like in the pull up blades, waiting in the part someone drives a truck or a forklift into it and say, oh, we’ll get

another one. Oh, we don’t have another one, because this is a brand new prototype, blatantly only money. I even saw something fall off a ship container, fell off a ship one time on a project I was working on.

So I had like a six month lead time, this thing that fell off this year. But it was a cow. Yeah. So it did really start to feel like I was I was CRST gods. So you got enough problems of your own, you know, and you’re trying to develop a new technology.

You’ve got technological problems that you’re trying to fix, and then you know that so much can go wrong. I don’t think it’s normal that as much goes wrong as what I experienced personally. But yeah, definitely, I imagine I wonder if this is a prototype later and there’s someone, you know, just like me sitting there going, why?

Why did this happen? Yeah.

Yikes. That’s crazy to think. I mean, obviously, like a lot of the stuff is in the news and you know, some of it’s not. But there’s so many out that these things are going to happen. So it’s an interesting article on wind power engineering and recently about not a super exciting piece of technology, but this ursi inflatable

cover that goes on the top of wind turbine towers as they’re being constructed. You know, like with construction, you see when there’s a huge storm, these poor construction sites are just like muddy. And so but I mean, how much of these towers, as they’re going up and like the blades and transport, how much of them are sensitive

to the elements, Rose-Marie? Like how much they didn’t need to be protected? It’d be like, look, we don’t want any issues 10 years down the road. So, you know, do they have to really work hard to waterproof these as they’re in transport?

Do they need to be heavily wrapped up? Like what are some of the the kind of the behind the scenes as far as protecting a whole construction site or the blades from Mother Nature?

Yeah, well, so they’ll often cap the end of the blade with something so that water doesn’t get in. But it does actually cost some money to, you know, install that column tarpaulins or actually the Danish accent was always the toppling, toppling them.

Talk the lane. For a long time, I was like, oh, it’s some sort of combination tarpaulin, trampoline. But actually, it was just that, you know, the English wasn’t anyone’s first language. And that’s how they were pronouncing it was very cute.

They cost a bit extra and a lot of customers don’t want them. So then you say like little bits of rust, because even if you’ve got stainless steel for the metal components, you know, you still get some rest, especially surface rust.

And then the stuff I was working on always had electrical equipment inside it because it was heated blades. And then you definitely, definitely want to cover them up because otherwise, I mean, they just get filthy. Aside from anything else and also, I mean, these wind turbines are designed for onshore or the ones I was working on.

But they’re going on a ship first, probably so they’re they’re exposed to a lot of salt Seaspray. But they’re not designed to withstand those really salty environments. So it is actually a bit of a bit of a challenge to to.

It’s designed for its operational life, but you’ve also got to make sure it survives its transport life. Yeah. And I guess that they’re experiencing similar issues with the towers. I was surprised to say that they need a roof because they’ve got a door at the bottom.

It’s not like they’re going to fill up with water, but it must be a problem. Otherwise, you know, we wouldn’t have this solution.

Offshore is the biggest thing ever right now. It’s booming. So more and more blades are going to be carted farther and farther offshore. So there’s probably just going to be a big influx of these sort of protective technologies.

I mean, is that something you see was probably just going to be necessary? Because especially if they’re taking blades out there and then there are some delays or this and that, there’s going to be probably more blades waiting in hospital, inhospitable areas as as I.

Am I kind of on track there? Yeah, I think so.

And I don’t have direct experience with with offshore yet. I hope to get some. I think we’ve got some projects coming up in Australia in the next few years. But in a way it would be an easier problem because all of the materials are already need to be up, specked a lot to go offshore.

So, you know, they’re like if they’ve got steel, that it’s going to be a really high grade stainless steel. So, yeah, and it’s also very obvious to everybody that it needs to be protected, whereas with onshore stuff like there was a lot of times when customers know that we don’t need this, it’s for, you know, it’s for

onshore and and then we’ve got it.

So like that, it’ll be fine. Effect is probably not in play as much for offshore. Everyone’s probably like, we need to make sure this is it’s like one and done and we’re not having any problems moving on. So we’ve been talking too much about recycling recently.

Obviously, we had Chris Howell from Veolia on the show talk about some of the awesome things they’re doing. But there’s a lot of recycling in the news cycle right now. Siemens Gamesa is targeting fully recyclable wind turbines by 2040 and fully recyclable blades by 2030.

Vestas is also, you know, right down the same path. Everyone’s got their own initiatives, it looks like. But Alan, it’s also tossers to you first. One of the things Vestas is is interested in doing, and they say they can do this with the SciTech solution, which that CFTC.

But they’re trying to Chem. cycle some of these epoxy based materials like obviously like winter and blade and to process them down and essentially re utilize them on like a molecular level. So obviously, both of you have talked before about, you know, epoxy resins and thermostats.

Like when they cure, they chemically change. And you can’t just melt them again like they they’re just different. They’re not like a big a plastic that melts and then can just solidify. So this idea of can cycling, that sounds kind of an off counterintuitive is the word, but it sounds like this hasn’t really been done before.

Alan, is this something that’s going to be viable?

Well, I don’t know. Yeah, that that’s the interesting piece about the I tried to dig into this a good bit over the last week or so to see what the engineering is behind it. And I didn’t really see a lot.

It sounds like Ollan, which is a thermo set manufacturer, epoxy manufacturer, is saying that they can basically re undo the crosslinking that happens in epoxy, that makes it so hard and tough and durable that can somehow break those bonds and bring them back into the constituent parts.

That doesn’t make a lot of sense because no one else on the planet is doing that. So maybe they have some unique chemistry that allow them to, I don’t know, hit it with a laser or hit it with some special heat source or something of the sort to to break the chemical bonds and get the the pieces

back, because there is this weird chemical change that happens. So the the technology is interesting, but no one’s talking it out. And I even did a quick search of patents to see if anybody had, you know, even slipped and maybe put an application.

And I didn’t see a thing there either. So I don’t know if it’s real technology. Is it still in the laboratory, as the UK people would say, or is it or is it just something that we it has been there the whole time and we just haven’t paid attention to?

I’m not sure where this technology is right now. Rosemary, do you have any idea where where they’re going with this?

Well, yeah. They told you you missed it in the infographics. A little pair of scissors next to a Poma. So they’ve got they’ve got very tiny scissors. They’re getting in there and snipping those crus links. But I just love that.

I mean, it’s it’s there’s a lot of words in the announcement and. Yeah, like it is absolutely a revolutionary thing. And they’re like, oh, yeah, we disassembled the epoxy. It’s like step one, and then I talk a lot about a lot of other stuff, I’m that, wait a minute, you disassemble the epoxy like please, please go on

, because you obviously that’s the crucial step that no one’s been able to do. And I think I described it the last time we talked about about them assets. I said, you know, like it’s like trying to fry an egg.

You know, there’s there’s a reaction that’s happened that’s not so easy to undo. And yeah, I don’t know where they’re at to sometimes people, you know, company PR departments want to announce things very early. So perhaps it’ll go nowhere.

But I mean, I really hope that it is going to go somewhere because, you know, if you can disassemble a epoxy after it’s set, then, yeah, we can recycle any kind of composites. And that includes the 95 percent of composites that don’t come from wind turbine blades that come from, you know, airplanes and cars and boats and

sports equipment. So, you know, like it’s way bigger than the the wind industry if if we can disassemble epoxy resin now.

Yeah. How come Elon Musk hasn’t talked about this? Because they would love to get some composites in the cars. And we use composites in aerospace all the time. Probably way too much, honestly, and we don’t really have a way to recycle them.

So if that technology is here, then someone needs to speak up, because you’re right. Ninety five percent of those composites, the poxy things are getting grinded up and ground up are put in a landfill. That’s where they’re going.

So let’s go. Well, let’s see what this technology is. And I, I just haven’t seen anything. It’s it’s crazy.

Well, I guess one of the follow questions is, would this end up? And I’m sure we’re just speculating, but would this end up cheaper than other forms of recycling it? Like we’re always going to need Samant, which is, you know, what Veolia is doing is a going outcompete, grinding it up and turning it into Samant or, you

know, burning it in the cement kiln or I don’t know what other methods of recycling there might be for it. But does this sound like something that would be really expensive or does it sound like once it’s a once a breakthrough is here, it might be really, really easy and inexpensive.

I’ve got literally no clue. It could it could be incredibly expensive or it could be incredibly cheap because it’s really like I don’t know. You might as well say that we have invented a time machine for as much cluh as I’ve gotten, how they’re actually going to to do this.

So. Yeah. Yeah.

But the the cost may not matter too much because like in Germany, where they’ve outlawed the bearing of a wind turbine blades, then you don’t really don’t have any options. Right. You’ve taken the grind up and Bériot solution off the table.

Now, regardless of what the cost is, the cost of all of it’s just jumped dramatically. Obviously, when you do that. So now is is this new technology with a little bit of scissors cutting these cross-linked apart cheaper than whatever else would be?

Maybe it maybe once you skew the market that way by putting restrictions in there, that you have to rethink the economics. And maybe there is an economics to it. Obviously, Vestas thinks enough of it that they’re going to pursue it.

So that makes just Vestas doesn’t play around. And that’s my impression of it, is that they’re really serious company. And Oatlands a very serious company. So you’ve got two very serious companies and some universities that are working on this.

There must be something to it, but please let us know. I think we’re just going to follow it.

Yeah, I think that normally, like if it’s being announced, you would expect that they have it to the point where they know it’s going to work eventually. But on the on the other hand, sometimes you do have a particular need for an announcement and you can get pressured into announcing something that you, the engineers, might rather not

say. Yeah. It’s just so different to, you know, like everybody else is really pushing, like really trying hard with them and plastics. And you wouldn’t bother trying hard with them spastics if you if you had any inkling that there was going to be a thermostat solution coming up in the next decade, then you would go that route

because it’s just so much structurally better and more like what we already know. So I’m kind of yeah, I’m suspicious that this might have been announced too early. I doubt it’s going to be just around the corner.

So let’s ask the obvious question, which is an Rosemary, you’re the perfect person to throw this question to. I think if if you’re making a composite structure and you have recycled epoxy components, does that make you stay up at night?

Because it would me and I’m not in a sexual person.

Yeah.

Like I’m taking these components, which may have some unique variability to them that I don’t know because I don’t have any history with it. Do I just reincorporated into my next generation of blades or is it just a ton of work that has to be done to requalify this new material?

Yeah, it’s a ton of work to qualify and new material. And it would be considered a new material. They wouldn’t be like, oh, we’ll just throw this into, you know, whatever we did with the Virgin material before that, because I believe that they’re separating the fibers out and have the resin.

Separately, so then they’ll be doing lab tests, they’ll start off probably with very, very small, just fiber fiber tests, then they’re going to probably make some some laminates and test small pieces of that, you know, lots of them enough to get statistics and say what the variation is, and then they’ll move up to larger components and eventually

reapply. So now I wouldn’t be worried about how they’re going to be used in the end, but it will be a lot of time and it costs a lot of money to qualify our new material. It’s also true for any you know, you want to change your supplier of your glass, you or your carbon fiber.

You have to do the exact same thing. So I think it will be a normal process.

Well, how long would you suspect that? I mean, that it would be kind of like some I know some classics like they have a certain amount of times they can be recycled. Right. Like they can’t be infinitely recycle.

They they degrade a little bit over time. And to those plastics get recycled to the molecular level, though? Probably not. I’m not. Certainly no plastics expert. But does this seem fundamentally different than that, where this is just like, well, Alan, you’re nodding your head, so I

sort of like you, like you go to you go to a DIY store. I don’t know what you call it in Australia, but it’s like Home Depot, a hardware store in America, and you buy some epoxy. Right. And there’s two tubes.

There’s there’s two pieces to it. There’s a hardener. And then there’s the epoxy sort of. You mix the two together in a WAMMO, right, so you get this thing hardens, and so you’re basically undoing that and putting the the solutions back into the tube again.

There has to be some chemical change that has occurred in there. It can’t be like virgin material. It won’t be. And that’s what scares me a little bit, is, you know, where that material ends up. I think the aerospace community will just say no, right there will just say, no, we’re not doing that because we don’t have

a 20 year lifespan on the material itself. That’s that’s the timeliness part of it. And how much effort and money is going to be spent into it, because you don’t know what you don’t know. And until you put it out in service for a long period of time, literally 20 years of beating that blade apart or an

airplane apart, you’re just not really confident in what’s going to happen there. So even in in the airplane world where we do structural testing and we have a pretty good, confident feeling that this new material is going to work just great.

It doesn’t always turn out that way. Right. And I think just because these wind turbines are getting so massive, the cost versus the risk starts to play in. Maybe it’s not worth the risk. Maybe you maybe you can’t break the material, the epoxy into its original pieces, but maybe you’re making something less risky with it.

That would make sense to me, like making a bathtub or making some sort of, you know,

other plant or planters that are fiberglass planners or like even like the shell for like a drone like. Right. A lot of these DGI drones are plastic, doesn’t seem structural or, you know, moderately structural at best.

Right. Yeah, probably

a lot of it. low-Impact OK. So there

you go. Or make the cells out of and make the cell covers. Yeah. Things are not really structural. Yeah.

Yeah. I was just going to say this. There’s more and less structural components in a wind turbine blade or wind turbine as well. So, yeah, and the cells are good ideas also, you know, vortex generators or maybe ranges.

And inside, you know,

plastic Slydini playgrounds,

we can already shred composites and make like boats and other, you know, like really garden furniture, stuff like that. So I do think that this has a potential to be, you know, like a a level above that. But yeah, let’s I don’t think that the first thing they’re going to do is just make a whole wind turbine

blade out of these recycled materials. I think that will be somewhere down the line. But I’m sure that’s the goal. Right? I don’t think they want to. Yeah, a lot of times what they call recycling of composites is really just finding places to hide the hide the stuff so you can hide it in cement or you can

hide it in landfill. Some not not necessarily a huge difference between those sometimes.

Yeah, well, it’s where that you start to think of recycling as that thing becoming that thing again. But it’s probably not the way most recycling is right now in most cardboard probably doesn’t become. Well, carbon might be a bad example, but most things probably become something like you said, something lesser that’s less important, less stressful.

Just as long as I find some future life, then it’s been recycled. And that works for everyone. Right. So I will keep an eye on it. Next up, we’ve got the Jones Act, very exciting United States policy, which is going to come into play.

Increasingly more because there’s a lot of nonuse, companies like Austan who are big players and there’s a lot of things coming over from overseas where offshore has been. You know, it’s well-established and it’s all being brought here to the U.S. So the Jones Act, which I had to read up a bunch on, is it basically.

So I’ll read it a little bit here. It restricts the transportation of merchandise between two points in the United States to qualified U.S. flag vessels. So if you’re a certified coastwise qualified vessel, then you can transport merchandise between U.S. territorial waters, which are about three nautical miles off the coast.

So this comes into play. Alan, let me I’ll have you jump into the fray here. Where did this come into play recently and why are people talking about this Jones act as far as qualified versus non-qualified vessels?

So it has to do with using U.S. flagged ships. And there’s not a lot of U.S. flag ships anymore. A lot of the things are import or exported. So the destination of origination is out of the United States.

So they’re flagged out anywhere. And South Korea being one of the big places. So what? But once you start motoring around wind turbine components within the states, it forces you to use essentially a US ship. Now, that’s not going to be the cheapest thing.

Right. And what everybody starts worrying about is I got all these added costs that are coming on. I could have hired a I don’t know, a Vietnamese ship or a Sudan ship or something to move my wind turbine from Florida to Boston.

Now, I can’t. Right. And that’s the difficulty. And there’s a lot of because of the profile of wind turbines, you’re going to have a lot of oversight because the unions are involved. You can have a lot of oversight and they’re going to.

Penya, every time there’s any indication you’re trying to skirt the Jones Act in the United States, someone’s going to be calling the Congress person and complaining about it. So there’s an inherent cost structure when you do that that’s going to start escalating the costs of wind turbine installations in the states.

And one of the discussions is, do we start building our own ships? And I think there was Dominion Energy was talking about building a ship, building a new ship, just to install wind turbines with that. Wow. That’s odd because the United States hasn’t been a shipbuilding country since essentially World War Two.

Shortly thereafter. But we may again. And that’s so when you talk about building the infrastructure, not only the US can’t be the only country that does this. I would imagine most countries are very strict about this. It’s just like flying on an airline.

Let me give an example on the airline. If I fly from I can’t fly Air France from New York City to Los Angeles, I can’t do that. Right. I can only fly an American carrier to do that. I can fly Air France from Paris to New York, but I can’t take a foreign carrier inside the United States

. And most countries are tend to be that way. So you wonder what I’m wondering is going to happen here, because a Jones act has been thrown around a lot in the halls of Congress saying this is a Jones act.

I can. Protect my state and get a bunch of jobs. But then the forces of politics come in and say, OK, you know, the the big construction companies are going to say, I don’t think that’s a good idea.

And, you know, the laws are meant to be changed. And this is one of them that I wonder won’t get changed before the offshore wind really gets big, that they’ll flip it and say, well, in these particular cases, if you’re more than three me through three miles offshore, it doesn’t we don’t care.

You can do whatever you want. That may be what happens, because I don’t see adding a lot of costs into the offshore wind right now. Just don’t see it.

Yeah. So more specifically, the ruling from U.S. Customs and Border Protection. It’s about the mixed use of some foreign barges and U.S. barges. I guess it’s what’s complicated about is that they’re constructing this someI submersible hull for an Ilave 11 megawatt wind turbine.

It’s being assembled in Maine. And then they’ve got to sort of drag it off into the water and then use this combination of foreign and U.S. flagged barges to then, you know, submerge it and anchored to the seabed.

So that’s where it gets complicated, because it’s not all U.S. barges helping to get this thing into its final resting position. And so some of this ruling was basically because the barges are used as a platform and not really transporting it.

Covid CBP is saying that they’re not violating the Jones Act. And so they’re going to allow the barges, the FA and wants to move away from the dock and then come back as long as they return to the same port and all the towing is going to be done by coastwise qualified tugs.

So those are, you know, a U.S. flag tugs. So it’s not really like a Chinese tugboat helping to push a bag out. There’s got to be a U.S. flag type. So really kind of a complicated, interesting stuff. So, you know, with this complex issue of just getting these turbines into their final resting place offshore, I know that

sounds like they’re dead, but they’re very much alive. Part of that process is getting the sea floor mapped, identifying, you know, the bedrock that they’re going to either be anchored to or the spot they’re going to be floating above, whatever.

So one company called Bedrock is using some interesting submersible drones that are going to help map the ocean floor just a lot more. What’s the word here? Well, efficiently, no. One, but they’re going to provide essentially almost instant access to ocean floor data is what they’re claiming, which is really interesting.

So, Rosemary, obviously there’s a lot of logistics, like you said. I mean, from every aspect of this. But it seems like this sort of technology we’ve talked a lot about aerial drones, companies like Sky Spects and many others are doing a lot to help maintain wind turbines.

But now that we’re offshore, much more in a global sense, with the U.S. coming into play, it seems like the submersible drones are going to probably have their day.

Yeah, actually, when I read this article, I was like, oh, yeah, that’s so obvious that why haven’t we been doing that for a long time? So, I mean, obviously, I don’t know why it was it must have been harder than it seems for it to be, you know, just coming on now.

But it does seem very useful, because I know that that’s like a really lengthy part of the process is mapping the seafloor and not just for offshore wind as well. There’s all sorts of things like I’ve been following this project in Australia called Sun Cable, where they’re going to put in a gigantic solar farm in northern Australia

, plan to put a subsea cable all the way to Singapore to supply. The theory is or their idea is, again, to apply like 20 percent of Singapore’s electricity from the Australian desert. So, I mean, it’s a very interesting project.

And I’ve been following it because it’s sort of like audacious. But I have noticed that, you know, the cable length started out, you know, like I was going to be a 3000 kilometer cable. Then it was a three and a half thousand kilometer cable.

And it’s kind of going up and up because as they map the sea floor, they find that they can’t do the route that they wanted today. And I’m not sure that this drone will work for that project. I think this one only has a maximum depth of like 50 meters or something.

But, you know, as the technology improves and I guess that it is going to help with subsea cables and and anything else that we want to do to the the ocean floor. So I think it’s really yeah, it’s a really cool innovation.

Also bedrock, actually. They’re claiming they can operate in depths up to a thousand feet and they can venture off to fifty six miles. It seems like 50 meters or 160 feet is about the max depth for a wind turbine where it can be installed.

So it seems like bedrocks well within that. So, yeah, they’re they’re excited about the mean. Now, Allen, does this seem like this is a game changer or is this something that’s maybe still going to take a little bit of a bit of time to roll out and it’s kind of full version?

Well, I. I think it’s going to be a big game changer because of two reasons, one, if you can really determine what the seafloor looks like, you’re going to stop a lot of damage to your cables. Right. That’s one of the early on between the United States and Europe.

They’re always trying to lay a cable. Right. So you could have the first telephone conversation in someone and in London. And the difficulty they had was you’d run over these rough parts of the ocean floor and the cable would break or there’d be a storm in it, run over these sharp rocks and it break.

So knowing where that cable goes is is really critical because you get so much money in the cable. Those cables are not cheap. And then you got obviously all the ships to spool them out and the whole thing.

You really want to put them in a even even if it takes a longer route to get there in the safest possible place for the longest period of time. And right now, you don’t really have very accurate data.

So they’re kind of guessing at it a little bit. And I think that’s I think that will dramatically lower the cost, because if you’re an insurance company and you’re underwriting this underwater cable, that’s your worst nightmare, that a storm comes and it gets severed in half.

Or if they get across something that’s particularly sharp, like an old battleship and then blammo, you know, the cable breaks. And I think there’s an opposite sex, I think on the United States. I think another thing may happen, which is off the coast of New England, there’s a lot of shipwrecks over there from whaling ships back in

the day to more modern things. And so, you know, you don’t necessarily want to disturb those because we consider to be gravesites, a lot of them because sailors were lost. And so you don’t disturb them. And I’m wondering if also you’re going to see a lot of conservationists come at it and say or national bodies like the

Navy or something come in and say, this area sacred. You can’t lay cable in this area, stay out. And the same thing. Also, if they determine there’s some sort of reef or some underwater structure that that’s for, animal life needs to be there or

the lost city of Atlantis, we might now find it. And you came up with a win win for him on that. Let’s see. I mean, come on.

Well, yeah, you know, because this relates back to I think this technology was developed when they lost the was that MH 370 aircraft that the triple seven that went off into nowhere and they never really found it. And you know how hard it is to find something that massive in the ocean.

It’s it’s damn near impossible, which is why they really haven’t found anything yet. But we’re through these mapping technologies. It won’t take long if we get the technology right and we start deploying them in the and the number and quantities, I think they will.

Now, we’re going to find a lot of things that we thought were lost that I think that will happen.

Well, that’s a really good point about that, about that plane crash, because how many years ago was that? Three years ago.

Something more like 10.

But it really.

Yeah, it’s been a long time.

OK. But either way, it did seem odd. It’s like, oh, we know approximately where this went down. This is a big flight. This was not like everyone knew this happened and we still couldn’t find it. And that does seem crazy in today’s age, that a huge plane with its I mean, debris, you find one, you know, one

piece of debris from this huge plane and you have a general idea of where it is now. Right. But still couldn’t find it. Yeah. That it’s kind of kind of baffling. So, yeah, you wonder about the implications with that with with all this offshore wind and just I mean, like camera let resolutions have come so far in

the last 10 years. I mean, there are still people who are, you know, work in video who are, you know, probably only 45, 50 years old, who were probably started out their career snipping film. Right. I mean, camera technology has made huge changes where it’s smaller and more powerful than ever.

You know, we’re recording on Merel mirrorless cameras, which are rapidly replacing diesel cars. And so the things that, you know, we should be able to do is is is going up bargo a step function. And I think one of the thing that’s interesting here, I know, Alan, you you just you love data.

You’re just such a data nerd. But they have their data platform already. Bedrocks is called Mosaic. And that probably solves a lot of problems that were also present five, 10 years ago, that, you know, if you got all this data or you just had a, you know, a tiny little memory card or however they would have done

it back before storage was what it was. So Rosemere, I mean, do you feel like this is. I mean, do you think this will fundamentally change where we install offshore wind farms, though, or probably not or just make it easier?

Yeah, I think it’ll speed speed it up. I don’t think it’s going to solve any of the the the real challenges, you know, trying to get the foundation in place and deep water and, you know, make sure that the cables.

Right. So we’ll probably also be able to, you know, what do they call it, an oil and gas prospect better. So, you know, you might be able to try and test out more sites before you can choose the one that’s going to be the cheapest, because I imagine that currently it’s probably not unusual to be surprised at

how much it’s going to cost you to get your cables in place. And maybe some found. Asian surprises, I guess it’ll cut back on uncertainty, and I think it will save a lot of time just good because, you know, the planning time frame on new offshore wind farms, it’s so long.

You know, I’ve been hearing about these ones coming in in Australia for already a year or two, and they’re still know, like several years old. I think a really, really key that has to get out that it’s. Yeah.

So anything I can do to to smooth and hasten that process is going to be really welcome, I think. Yeah, well, I

mean, even in today where we feel like we have everything solved, there’s still this crazy building in San Francisco. I’m not sure if you both have heard of it, but the Millennium Tower in San Francisco is tilting. It’s sinking and it’s tilting.

This is like a luxury building, like, you know, celebrity athletes. I mean, this was a really luxurious high rise in San Francisco. And they’re currently putting a hundred million dollars into it to try to prevent it from tilting and sinking.

It’s currently like twenty two inches tilted. So and that’s onshore in the daylight in San Francisco. So then, like you said, you think of these challenges where it’s pitch black at the bottom of the sea and you just don’t know what you’re getting.

Now, getting into down there, you can see a just difficult and so much there’s probably so much unexpected stuff happens that the public just doesn’t isn’t privy to. So I think you’re you’re dead on that. This will probably make things just a lot easier as as a submersible technology continues to to evolve.

So last on our on our our docket here is this open hydro tidal turbine, is that the EEC, the European Marine Energy Center, they’ve been removing this from it’s they’ve opened a tender for the removal of this turbine.

So, Rosemary, you’re I think our champion of all these not only wind power things. What are your thoughts on this titled turbine and tidal power in general?

Yeah, well, I so I did a few videos on my YouTube channel about wave energy, partly just because I was surfing at the time. And I’m like, oh, my God, there’s so much power in these waves. And yeah, like why isn’t wave power a thing of say we’ve been hearing about it for decades and title is kind

of similar, although the, you know, common idea is that it’s much simpler because it looks just like a wind turbine. Know, like wave energy is hard to extract the energy because you’ve got these like linnear motions mostly say up, down or fought back.

But tidal just, you know, turns a turbine very similar to a wind turbine. So it seems like, you know, a nice, simple way to deal with it. But when I was reading about this decommissioning and what happened to this particular technology, it was very similar to what we say with wave energy technologies.

You know, this, that I could not find anything wrong with the technology. It seems like it was working. It was, you know, making energy, delivering it to the power grid. They had some sails, but it was just costing so much money to develop.

There were, you know, in so much debt, because every time when you develop the technology, things go wrong all the time. You need to go out and fix them. It’s one thing if it’s a wind turbine or a solar panel, it’s sitting on the ground in some conveniently located test location.

Another thing, if it’s in the ocean and this site in EMAC in I think it’s in the Orkneys, it’s a really, really beautiful location that I really want to visit and go surfing there. It’s it’s there specifically to take away some of that pain.

You know, it’s a test site there where like all the infrastructure in place, you know, you just drop in your new equipment. It’s very easy to do a grid connection. They’ve got infrastructure there so that you can easily take it out of the water to maintain.

So they’re trying really hard to smooth that as much as possible for ocean technologies. And yet this this technology, nothing particularly wrong with it. I’m sure it would eventually work this cost too much and. Yeah, one thing when I was talking, one of the interviews I did for for the YouTube videos was with a couple of researchers

from the University of Western Australia. And they said the thing with wave energy is that you need patient money, you need patient investors because it just takes so long and cost so much money. You know, you’ve got a cable break.

Maybe it’s an off the shelf cable. It’s not even your thing. You’ve got to replace it. You know, it’s still you had to wait for a weather window. You’ve got to get divers out there, you know, like it’s just you just burn through money and that early phase well before you’re going to start recouping from a lot

of sales. And so I think that that’s just yeah, it’s just another story of a technology that didn’t there’s nothing particularly wrong with the technology. Could have got it to work, but just just not economic. And I mean, I want to do we do need do we need these things is, you know, we’re trying so hard with

with wave and tidal isn’t, you know, solar and wind and storage enough by now?

I don’t know. I feel like you’re the diversification person, though. I feel like that’s out of character now. I mean, should we should we get a little trickle from a million different sources?

Yeah, and I think so one thing that you hear a lot when you’re talking about different kinds of energy technology is people say, you know, it’s not about any technology winning. We need them all. And I kind of agree, except I don’t think we need them all.

I think we need a variety, but we don’t need all of them just because you can make energy from, you know, like a shake, a flashlight. It doesn’t mean that that’s going to be a part of our, you know, renewable energy future.

So we need a diversity, but we don’t need every single idea that someone has doesn’t need to be part of the final. The final what water system? Yeah. So but you’re right, I am today being uncharacteristically negative about it, because I do think that if there’s any time for full wave or ocean energy, it’s it’s now.

But I’m still not sure that it’s ever going to be that time.

I think this is interesting because this ties into offshore wind so nicely in that the maintenance is the key and how much is going to cost to maintain these things. Right. And I know on offshore wind, that’s one of the big concerns, is that you have to have this crew of people at a floating hotel that constantly

maintain these wind turbines. And how much is that going to cost? And if these cables break in, the turbines, starts floating, how much is that going to cost? It’s not just the manufacturer of the component, it’s what you do or the 20 year lifespan that matters here.

And offshore, offshore wind and tidal energies always seem like they’re synched up in this weird way, which is you’re never really sure how much you’re going to spend on the ocean. It’s just such a rugged environment and the sea floor changes and you got these weird things happen, any of hurricanes or typhoons, and you have weird, weird

shifts in the Teutonic plates and God knows what else. So you just don’t know. And I think I think with title, it has kind of run its way in that the maintenance is going to kill it. You can you can do the engineering, you can put it out there.

But just it’s so costly to fix it. You can’t do it logistically. But offshore wind were like, you know, well, we’ll make this work. I’m not so sure. And I think this is why companies like Blade Bug, she’s losing track of who a rope, robotics arounds, sky specs, all these companies that are doing the robotics are so

critical. The success of offshore wind, it’s not just making the turbine and floating it out there, its ability to repair it, maintain it and keep it operating. It’s going to be key to making it successful.

Well, and just to close the circle here, I mean, you know, Open Hydro was installed back in 2006. This was 15 years old, and they were to a 250 kilowatt turbine. And, of course, the Orbital Marine O2, which we talked about, you know, a couple of months ago, that’s a two megawatt turbine, much different design.

Right? That looks like a it looks like a 777 airplane that you parked in the ocean, essentially, you know, the waves pushing its propellers. So there’s that newer iteration is out there and maybe that’s more durable, maybe that’s more cost effective.

So it’s there’s definitely some they they’ve made a lot of progress. And like I said, that’s a very different design. And that just launched this year. So. And Rosemary, I don’t think you’re for the record. I don’t think you were.

I thought you’re being pretty charitable about it. That is the way it is worked. It just didn’t just didn’t pan out financially. And I think there’s probably a lot of things that have been like that, right, where I mean, all the older turbines are were so underpowered compared to now that maybe they just did their run their

course and people got data and now they know, hey, maybe with new technology and new materials, what we did learn that one won’t have. Won’t have died in vain and give rise to these new cool ones, because though, too, is a really cool machine.

So we might have to use it. That one thing is cool. So. Well, that’s going to wrap it up for today’s episode of the All Time podcast. Thanks so much for listening. Be sure to check out the show notes where you can subscribe to Uptime Tech News, our weekly newsletter with podcast updates, as well as Rosemarie’s YouTube

channel, where she’s always putting out new renewable energy content. Be sure to subscribe to the show, to the show on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, YouTube, wherever you listen or watch. We’ll see you here next week on uptime. Operating a profitable wind farm is all about mitigating costs, minimizing risks and being efficient with maintenance, repairs and upgrades.

It’s incredibly expensive to send a team of rope access technicians up tower to make even simple repairs. We also know how costly lightning damage can be requiring inspection, repairs and downtime for even minor lightning strikes. Maximize the time efficiency of your techs and prevent future lightning damage by installing our strike tape loops upgrade the next time your

crews are going up on ropes. Learn more in today’s show notes or visit us on the Web at Weather Guard Wind.COM.